It is not uncommon to find artists who came to film from work in other mediums. Some are painters turned filmmakers, while others turned to film from work in theater or writing. German filmmaker Alexander Kluge’s path to film was as strikingly different as his work continues to prove itself. Just having turned 80 years old, Kluge is as radical as ever, and could still serve as a signpost for the young generation of filmmakers.

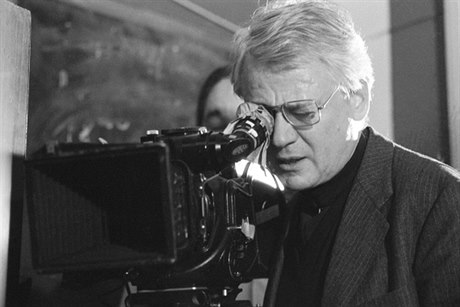

Alexander Kluge in Prag is a retrospective that covers the last 50 years in which the maverick German director has been forging his uncompromising artistic vision. The show’s curator, František Zachoval, told Czech Position that Kluge’s still too little-known body of work presents an entirely new perspective on the art of film, questioning the fundamentals of the film medium itself.

For Zachoval showing these films at Prague’s Academy of Fine Arts from May 17 through 19, their first screening in the Czech Republic, is vital for the coming generation of Czech filmmakers to be exposed to.

“His methods are almost totally unknown in the Czech Republic, which is why we are providing a broader presentation of his work extending from the 1960s to the present,” he said.

Zachoval also considers it very important to note that Kluge is not only a filmmaker and that his work straddles the lines between different mediums. “He occupies a position at the intersection of classic film, literature and subversive television production. This resistance to fitting within the confines of any medium is very important for the young generations of artists here to see, which again is why we’re showing a cross-section of Kluge’s work.”

Filming essays

Not only did Kluge not set out to become a filmmaker, he was hardly involved in the arts at all. As a law student Kluge came into contact with philosopher Theodor Adorno and served as a legal counsel for the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, where Adorno was active. At that point Kluge was writing short stories, but Adorno steered him towards filmmaking in spite of the fact that he wasn’t a great admirer of the art form.

Adorno introduced Kluge to Fritz Lang, who was filming The Tiger of Eschnapur (Der Tiger von Eschnapur). Kluge reportedly had less interest in watching the legendary director than getting off the film set and working on the short stories that would be a foundation for his early films.

Zachoval says that it was Adorno who remained the prevailing influence on Kluge, who would make his debut film Brutality in Stone (Brutalität im Stein) in 1960, a short work of montage attacking German amnesia towards its role in World War II and the older generation of filmmakers who let German society avoid the difficult subject of their responsibility.

Things came to a head in 1962 when the Oberhausen Manifesto was proclaimed by 26 young German directors that formed the New German Cinema movement. The battle cry of the group was “Papas Kino ist tot” (Papa’s cinema is dead) and besides Kluge it included a roll call of the best German filmmakers of the second half of the 20th century, such as Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, Volker Schlöndorff, Margarethe von Trotta, Hans-Jürgen Syberberg and Wim Wenders.

Stylistic evolution

According to Zachoval, Kluge moved past the use of collage and combining documentary and fictional shots.

Zachoval says that Kluge’s films from the ‘80s, including two of the films being screened in Prague — The Power of Emotion (Die Macht der Gefühle) and Miscellaneous News (Vermischte Nachrichten) — draw the viewer into a maze of small and, at first glance, unrelated events. Kluge’s films from this period can’t be easily summarized and don’t have a single, clear point. This is where he departed from the work of his compatriots as filmmakers such as Fassbinder, Herzog, Schlöndorff and Wenders have more or less kept to the classical dramatic form in their work.

“These more fragmented works are based on a single event, experience or insight and aim to evoke a process of association for his audience. And here his work is very radically near to the principle of literature,” Zachoval said.

The connection with literature is not surprising as Kluge has continued to write, and his work in this medium is regarded very highly as well. Though Kluge’s films are certainly radical and bypass many of the conventions of the medium, Zachoval insists that it doesn’t belong to the tradition of avant-garde filmmaking.

“His recent work has a closer relationship to philosophy, sociology and literature. In particular, his most recent monumental projects are clearly visual deconstructions in the sense of the word associated with Karl Marx and Martin Heidegger.”

Zachoval says that Kluge’s work does have some counterparts among Czech filmmakers such as Karel Vachek and Ondřej Vavrečka. As Kluge’s film experiments grew even more radical in the ‘80s, he departed even further from the academic quality that Zachoval sees as so prevalent among even the young generation of Czech filmmakers. Perhaps the exposure to a filmmaker who uses the medium to look at social and political issues rather than a neatly fashioned story will strike a chord here, and will influence the next generation of director to explorations of their own.

Alexander Kluge in Prag

May 17 – 19

Academy of the Fine Arts Prague

U Akademie 4, Prague 7