The past two decades of Czech and Slovak Surrealism are on display at Prague’s Old Town Hall in the exhibition Another Air: Close Your Eyes and Open Your Window. Besides the Czech and Slovak artists involved in the group there are works by an array of international Surrealists. From paintings of morphing beasts to collages made from porn magazines, the show carries the irreverent torch first raised almost 100 years ago.

Bruno Solařík, one of the curators of the exhibition as well as a participating artist, told Czech Position that he believes it is possible for ideas and aesthetics to become outdated but that in Surrealism he finds a way of thinking and seeing that has a more lasting value.

“From its beginnings, Surrealism was not a movement like the other ‘isms’ – Impressionism, Expressionism, etc. – but was dedicated to a dialectical process between passive and active attitudes to reality,” he said.

Solařík sees the idea of Surrealism as being an escape into the world of dreams and visions as another common misconception. “It’s the dialectical connection between reality and imagination,” he said, adding that there is a distinct difference between authentic Surrealism and the many surrealisms that merely try to copy what the Surrealists of the past have already done.

“In an exhibition of authentic Surrealism, you can see that there are many looks and shapes. There is not one ‘ism’ shape.”

Real reality

And while other aesthetic approaches may claim that they adhere closer to reality, Solařík says they do this at the expense of ignoring the subconscious. In this respect, Surrealism aims at a more “real reality” by having the artist go beyond what he knows about himself, and tackling the unknown.

“Jan Švankmajer says that the unconscious is so powerful that you can’t change it, but that it’s better to know what it wants to do with you,” Solařík said. For him, the variety of visions in the show is the inevitable result of artists not following fixed expectations, but of listening within themselves. “Of course everyone has his or her own monsters inside, and angels, so the shapes of those monsters and angels is different.”

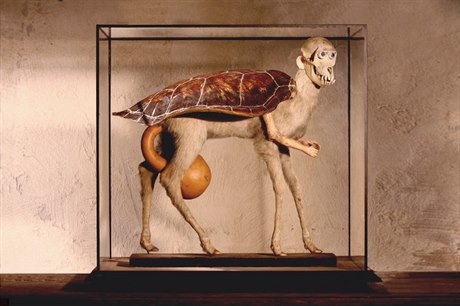

The exhibition bears this belief out with artwork running the gamut from the dark and haunting paintings of Leonidas Kryvošej to the wildly colorful canvases of Istanbul-born Israeli artist Ody Saban. In addition there is a significant amount of photography and sculpture in the show.

Kateřina Piňosová, a member of a group of Czech and Slovak group of surrealists since 1996, told Czech Position that among the Surrealists the mediums used can vary and because they don’t put any emphasis on whether an artist is professionally trained they are just as likely to move from painting to photography depending on what they are aiming to express.

The variety of the work on display is also clearly fueled by the diverse influences that go well beyond the Surrealist tradition itself. The paintings of Piňosová, for example, show traces of Native American and African art, though in an entirely different manner than was experienced by early 20th century artists. The paintings of Kathleen Fox resemble cave paintings in their texture if not in the sensibility they reflect. Other artists show traces of movements as diverse as postwar Abstract Expressionism, ‘60s psychedelia and even comic art.

The Švankmajers

The artists that hark back most strongly to the Surrealists of yesteryear are two of the most well-known artists in the show — Jan Švankmajer and his late wife Eva Švankmajerová. They manage to achieve this connection to the past without being in anyway derivative. Švankmajer in particular is represented by a wide variety of mediums and styles, but what shines through is a vital irreverence, such as can be seen in his Tactile Death Notice of Sigmund Freud, in which he overlays a photograph of the founder of psychoanalysis with chicken legs and clay ears and noses. Eva Švankmajerová participates in this destruction of idols quite literally in her sculpture A Surrealist Person Who Has Lost Their Face, in which a Roman-style bust is presented faceless.

The Švankmajer surrealist tradition doesn’t seem to be in any danger of disappearing as the paintings of the Švankmajer’s son Václav Švankmajer are some of the strongest in the exhibition. In his work he utilizes a firm technique to blend concrete forms with abstract splashes of paint, splashes whose red color is suggestive of blood splattered on the ground.

Twenty years after

Another Air comes 20 years after the last Surrealist exhibition, Third Ark, which had covered Surrealist activities of the previous two decades. Since that time the Czech Republic and Slovakia split apart, though Solařík takes special pride in the Surrealists’ ignoring this bureaucratic fact.

“There are only three organizations that still call themselves Czechoslovak – a trading bank [ČSOB], the Anarchist Federation and the Surrealists. We decided not to respect the border-making. Why should we change just because of the decision made by a handful of people to separate the countries?”

Solařík says that the Czechoslovak contribution to Surrealism dates back to its beginnings in the ‘30s and comes back to the idea of a tension between dream and reality. “French Surrealism has this as well but in Czechoslovak Surrealism the attempt to put a stress on reality and not just dreams was always much more powerful. It was this attempt to show that inside reality there is perhaps a more fantastic reality than inside the head that tries to make the fantastic conceptually.”

And while the French Surrealists put a lot of stress on “desire” as a theme of their artwork, Czech and Slovak artists had a far more oppressive experience over the last half century that resulted in a change of emphasis.

“When you are in a situation where you can do nothing your only possibility is to laugh at it, so black humor, sarcasm and irony became much more typical of Czechoslovak Surrealism than desire. Desire began to seem toothless.”

Another Air: Close Your Eyes and Open Your Window

The Czech-Slovak Surrealist Group

Old Town City Hall , Prague 1

To April 4, 2012