On a moment a hundred years ago today in which abstraction began to take shape

From our Art History books we learn that Post-Impressionism followed Impressionism, and that Impressionism was a reaction against Realism and Neo-Classicism, and so on and so on. And of course even the driest textbooks allow a role for individuals, especially when they’re geniuses, though even geniuses don’t seem to alter what is presented as one movement inevitably following another.

The abstraction which came about in 20th century art and music are often similarly taken as inevitabilities, as if it was only a matter of blanks being filled with artists’ names and dates.

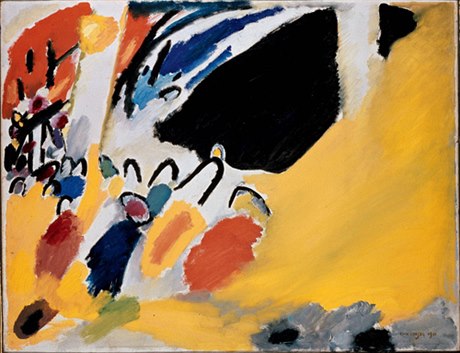

On January 2, 1911 the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky and his German compatriot Franz Marc attended a concert of music by Arnold Schoenberg in Munich. Schoenberg’s Three Piano Pieces and Second String Quartet were performed, and the two painters were stunned. Following the concert Kandinsky started sketching and a day later he painted Impressions III (Concert).

The music’s bold lack of tonality was what affected them so profoundly – and not only their ears, but their aesthetic sense and that something similar might also be possible in their own medium.

On January 18, Kandinsky sent a letter to Schoenberg along with some of his recent work. “You do not know me, of course – that is, my works – since I do not exhibit much in general, and have exhibited in Vienna only briefly once and that was years ago . . . However, what we are striving for and our whole manner of thought and feeling have so much in common that I feel completely justified in expressing my empathy.”

The letter went on: “In your works, you have realized what I, albeit in uncertain form, have so greatly longed for in music . . . the independent life of the individual voices in your compositions, is exactly what I am trying to find in my paintings.”

What follows is what distinguishes Schoenberg from so many of his contemporaries and what also distinguishes Kandinsky from many (largely French) strains in modern painting: “I am certain that our own modern harmony is not to be found in the “geometric” way, but rather in the anti-geometric, antilogical way. And this way is that of ‘dissonances in art,’ in painting, therefore, just as much as in music. And ‘today’s’ dissonance in painting and music is merely the consonance of ‘tomorrow.’”

Schoenberg wrote back with enthusiasm over the “points of contact” between them as well as about Kandinsky’s work itself. A few months later and the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) group was formed, inaugurating a great though all too short age of German Expressionism out of Munich.

At the same time the group’s extremely radical Almanac was conceived (which included contributions by Schoenberg) in which the art of the Blaue Reiter shared the pages with paintings by their modern predecessors (Henri Rousseau, Van Gogh, Gauguin), medieval German art, Russian and Bavarian folk art, African and Pacific island and South American art. The Almanac was edited by Kandinsky and Franz Marc.

The beginning of a collaboration and friendship between a musician and a painter might seem out of place in a literary blog, yet not only were there literary elements to the equation – they were vital features without which the link between the two arts might never have come about.

First of all, the ties between the two men begin with a letter in which Kandinsky expresses what he feels are their common aims. Even before that though words played a role in the birth of abstract art, as the promoter of that January 2nd concert well knew when he put a passage from Schoenberg’s book Theory of Harmony on the concert poster, a passage of which said:

“Dissonances are only different from consonances in degree; they are nothing more than remoter consonances. Today we have already reached the point where we no longer make the distinction between consonances and dissonances.”

And with the Blaue Reiter Almanac as the most comprehensive expression of that sensibility, including paintings, sculptures, essays, musical scores (one by Schoenberg, who also wrote an essay) and an Expressionist play by Kandinsky, the literary foundation of their work is evident enough.

One more thing – the art is referred to as German Expressionism, and a majority of its members certainly were German, yet at its founding moment there was a Russian painter that grew up in Odessa coming into contact with the music of a Viennese Jew. Sounds Central European to me.