The Czech government on May 30 announced it had earmarked another Kč 550 million for the Prison Service budget, most of which Justice Minister Jiří Pospíšil (Civic Democrats, ODS) found from his ministry. In addition, the service will get Kč 150 million from the reserve budget. Though it sounds like a windfall, the prisons had asked for Kč 940 million. Czech Position commentator and security expert Zdeněk Ondráček examines the dismal state of the nation’s prisons.

The situation in Czech prisons has long been tense and threatens to lead to full-blown riots. The main problems are overcrowding, a lack of funding and the expected amnesty in connection with the election of a new head of state, after President Václav Klaus steps down in March 2013.

Currently there are nearly 24,000 people behind bars in the Czech Republic, 13 percent above the institutions’ capacity. It is estimated that in two or three years the number will rise to 25,500. And there are some 6,000 people who are wanted by the police; if they were to be sent to prison, the system would collapse.

Supreme State Prosecutor Pavel Zeman, summarizing some of the main findings of a study prepared for his office, said in March that the cash-strapped penitentiary system is “in crisis.” Among his proposed solutions are requiring prisoners to earn their keep while incarcerated, reclassifying the types of prisons, and renewing efforts to allow for convicts to serve time under house arrest.

Lessons from Leopoldov

So far, the biggest prison riot in the country’s modern history took place in 1990, in the former Czechoslovakia. It was indirectly caused by the reckless amnesty granted from January by the first post-communist president, Václav Havel (the country’s most famous former prisoner). In March that year, 217 prisoners declared a hunger strike, and when they managed to get most of their demands (thanks to a grand uprising of prisoners), they occupied Leopoldov Prison (in today’s Slovakia).

At that point there were approximately 2500 inmates in Leopoldov, including some 200 murderers, 170 rapists, 370 burglars and 320 thieves, most of them falling under the provisions of paragraph 41 about serious recidivism and so not eligible for the president’s amnesty. They began destroying the prison.

Negotiations proved futile, and some 2,400 police officers and soldiers were brought in, along with armored personnel carriers and 80 police dogs, to crush it. Fighting left one inmate dead and dozens wounded, with the authorities battered and bruised as well. Five of the 11 buildings were burned, with damage exceeding Kč 30 million (no small sum at the time).

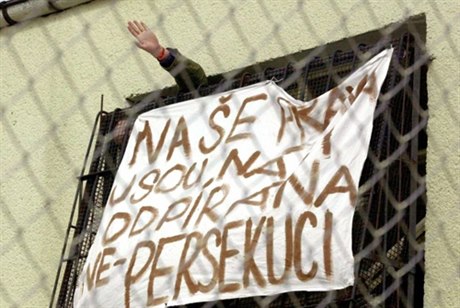

History could repeat itself, for a number of reasons. Many prisoners have been loudly protesting conditions, and some have even won disputes in the courts. It’s only a matter of time before the avalanche of complaints will result in sanctions against the Czech Republic for human rights violations. The Czech ombudsman, Pavel Varvařovský, spoke of the need for reform last year in his annual report.

Precipitate stripping

Another major problem of the Czech prison system is the funding. According to Justice Minister Jiří Pospíšil (Civic Democrats, ODS), the Prison Service of the Czech Republic can only ensure the smooth functioning of correctional facilities until the end of May, given the approved budget. So he asked Finance Minister Miroslav Kalousek (TOP 09) to release reserves from the Ministry of Justice for almost Kč 1 billion. The whole government decided upon it. The result was Kč 150 million from the government’s reserve budget plus Pospíšil found another Kč 550 million for the Prison Service — in total, Kč 200 million less than the prisons had asked for.

To ensure money for the next few weeks, the justice minister hopes to raise some Kč 250 million by selling unneeded property. But that would only be a temporary problem to a systemic problem. Furthermore, the planned sale will take place under pressure, and when the market is already unfavorable, so it will likely be sold at a disadvantageous price. Who will bear the responsibility?

Pospíšil has no support within the government of Prime Minister Petr Nečas (ODS) to make systematic changes to the prison system. Whether the premier realizes it or not, the problems require long-term solutions along with an immediate infusion of cash. Perhaps it stems from a behind-the-scenes battle between Nečas and Pospíšil, but what is certain is that a prison uprising could lead to the latter’s recall.

Pospíšil, however, cleverly and openly warns that the prison system is in dire straits and has shifted responsibility for that from his ministry to the government in general and Nečas in particular. Regardless, prison riots would not only hurt the government and the ODS but society as a whole, as a result of the extra cost to restore order.

How great an amnesty?

The third problem that could lead to unrest or spark an outright riot is the anticipated amnesty. In recent months, there has been much talk of a general amnesty for those having committed the least serious crimes. Again, this would reduce the overall prison population but cannot be regarded as a systematic solution to overcrowding.

Amnesty should not be granted just because the state lacks the capacity and means to keep criminals behind bars. Furthermore, it would also lead to a certain amount of resentment on the part of law-abiding citizens, who already perceive crime as being on the rise; voters would not looking kindly on the government in this regard.

With the final list of contenders to replace President Václav Klaus not certain, the scope of the amnesty is a matter of speculation, and so is the response to it. All that can be said for certain is that it will not be as grand as the one Václav Havel issued in 1990. But the Ministry of Justice and the Prison Service are preparing for possible unrest, or even riots, as is clear from the fact that Pospíšil submitted a new Act on the Prison Service that would grant prison guards greater power to act with force, with their status approaching that of the regular police. The bar for allowing wardens to use tear gas and stun guns would also be lowered.